Quick Links

Key Points

- The female-male earnings ratio for full-time, year-round workers stood at $0.74 in 2020. That represents a narrowing of about 2 cents on the dollar from 2019. This trend mirrors the narrowing in the Census Bureau’s newly-released official pay gap measure of 1 cent on the dollar over this time. At face value, the narrowing of the wage gap seems like good news. But, the analysis reveals the weaknesses of the methodology during uncommon times, and Gusto’s payroll microdata allows us to dig into determinants of this measure and causes of change.

- Looking by industry, the difference male-female wage gap is nearly zero in many service-sector occupations, where women make up a larger portion of the workforce. At first glance, the loss of these jobs during the pandemic might have led to a wider gender pay gap, as industries with equal pay made up a smaller portion of the overall sample of jobs. But because these jobs are primarily lower-wage and disproportionately held by women, the economy-wide pay gap in fact narrowed.

- The improvement in women’s relative pay came at the cost of women’s earnings at the low end of the wage distribution. Women in the bottom 25% of the distribution in 2020 experienced 18% higher separation rates than men in the same quantile, while men and women in the next earnings group experienced roughly similar separation rates. Because of the disproportionate separation rates of women in the bottom quartile of the wage distribution, women lost $1 for every $0.97 lost by men in 2020.

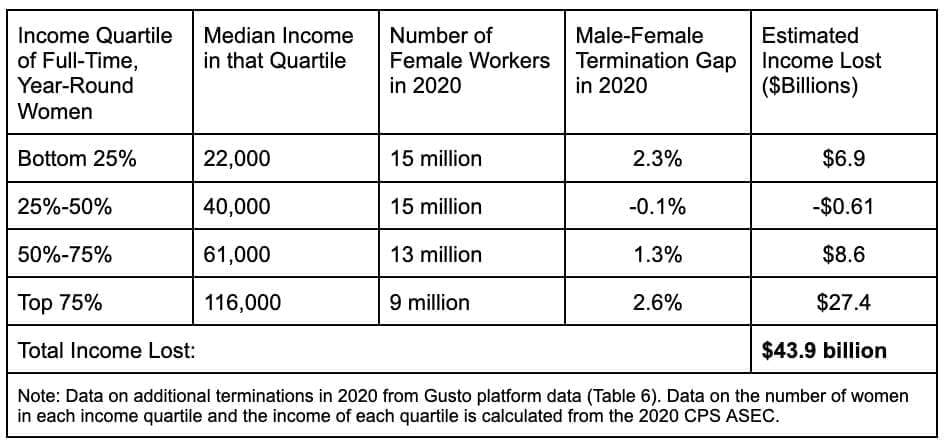

- If male workers had experienced similar termination rates across the wage distribution as women, the wage gap in 2020 would stand at $0.737 – that is, about 20% of the narrowing from 2019 to 2020 was due to disproportionate termination rates of low-wage women. Put another way, applying these higher termination rates to public data on the number of female workers in each wage group, we estimate that women lost $43.9 billion more than men in earnings due to higher separation rates.

- What this means: In 2020, the US economy saw a narrowing of the pay gap between men and women, but a significant part of this narrowing was in fact because of a deterioration in women’s economic progress: low-wage women disproportionately left the workforce as the COVID-19 pandemic hit the sectors they worked in the hardest and as caregiving responsibilities forced them to take a step back from work, artificially raising measures of women’s earnings in 2020. This unequal impact can account for one fifth of the apparent narrowing of the gender pay gap, and it resulted in women losing $40 billion more in earnings than men over the past year.

The Gender Pay Gap

Much attention has been paid in economic research on the disproportionate economic impact of the COVID-19 recession on working women. At the onset of the recession, from February 2020 to April 2020 — the official unemployment rate jumped to 16.1% for women compared to 13.6% for men – the largest difference on record. In this time period, the labor force participation rate also fell 6% for women while it fell 4.5% for men. Although these differences pose a substantial threat to the economic gain women have made in the economy over the past several decades, conventional measures of gender equality are not well suited to capture the changes that have resulted from the COVID-19 recession. In particular, the Census Bureau’s measure of the gender pay gap, on which data Equal Pay Day is based, showed a narrowing of the gender pay gap in 2020. In this analysis, we use payroll data from Gusto’s platform of over 200,000 small and medium sized businesses to examine a similar measure of pay equity and find that the apparent narrowing of the gender pay gap is largely due to disproportionate rates of women leaving the workforce in 2020.

In this analysis, we compare median earnings of male and female employees working full-time (an average of 40 hour per week each month) and year-round (employed 12 months). This methodology mirrors the Census Bureau’s method for calculating the gender pay gap, but Gusto’s payroll microdata allows us to dig into determinants of this measure and causes of change. Calculating this measure on Gusto’s platform data yields a gender pay gap of 0.74 — that is, in 2020 the median full-time, year round female worker earns on average 0.74 cents for each dollar the median full-time, full year male worker earns.

Table 1 presents this measure for the years 2018, 2019, and 2020. The gender pay gap narrowed slightly from 2018 to 2019, from approximately 71 cents per dollar to 72 cents per dollar, but then narrowed to 74 cents in 2020. While on the face this may appear to be encouraging news – women working full-time hours, year round were making closer to the earnings of a full-time, year-round male worker. But it is important to examine the reasons underlying this narrowing, to understand whether this represents a real increase in the relative economic power of female workers, or is a function of adverse trends not captured well by current methodology. We examine two potential reasons below.

Table 1: Female:Male Earnings Ratio, 2018-2020

Gender Pay Gap by Subsector

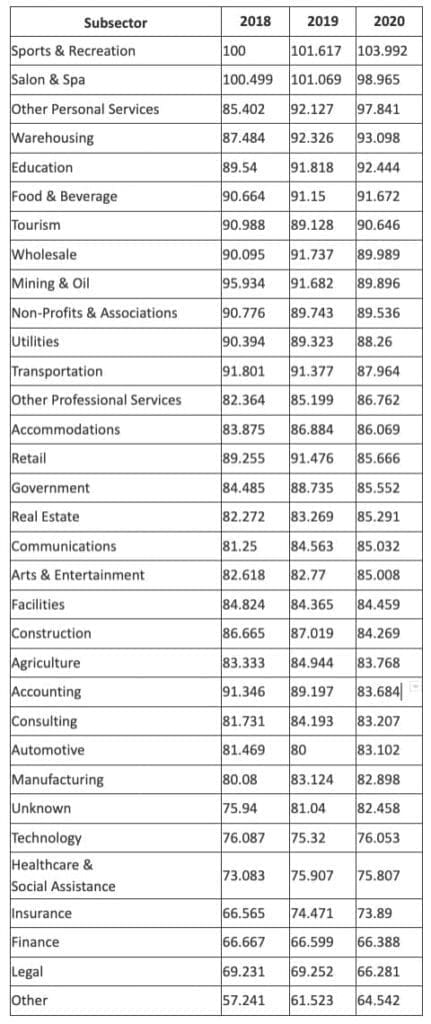

First, Table 2 presents this measure of the gender pay gap broken down by subsector, ranked by narrowest gap. Similar to other work that shows a wide gender pay gap across multiple dimensions, we do observe that there are virtually no industries where the median female worker outearns the median male. One notable exception, however, is Sports & Recreation, where women consistently have slightly higher annual earnings compared to men.

Table 2: Gender Pay Gap by Subsector, 2017-2019, by Narrowest 2020 Gap

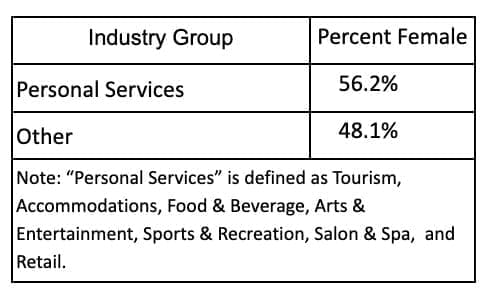

More generally, Table 2 shows that many of the subsectors with the most narrow wage gap are in personal services or Leisure and Hospitality, where women primarily work. Overall, as presented in table 3, a majority 56% of personal services jobs are occupied by women — compared to just 48% of other jobs (in Professional Services, or Goods-Producing sectors). In Sports and Recreation, the subsector with the greatest pay equity, women occupy 62% of jobs, and in Salon & Spa women occupy 85% of jobs. In contrast, in Finance, where there exists one of the widest pay gaps, women hold just 44% of jobs.

Table 3: Percent of Workforce Female, by Industry Group

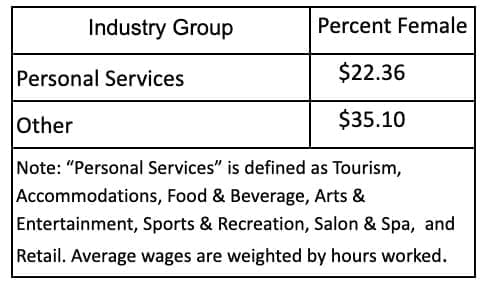

These trends are important because it is precisely these personal services jobs — in which working women are concentrated and which are closest to achieving pay equity — that disappeared during the pandemic. Counterintuitively, it might seem as though the disappearance of these jobs with near equal pay would have actually widened the pay gap, as the industries that survived have wider pay gaps. However, because these industries are also those with the lowest average pay, as in Table 4, as women in those jobs leave the workforce, women’s median earnings increase, in turn narrowing the gap between men and women. We attempt to quantify the effect of these unequal termination patterns on the gender pay gap in the next section.

Table 4: Average Hourly Wage of Females, February 2020, by Industry Group

The Termination Gap and the Gender Pay Gap

A large body of economic research, including prior Gusto research, has documented that women experienced higher termination rates than men in 2020, even compared to prior years. Table 5 compares termination rates for men and women on Gusto’s platform in 2019 and 2020. In 2019, female workers experienced termination rates of 19%, compared to 17% of men, creating a termination gap of 2.3 percentage points. In 2020, however, as the sectors in which women worked suffered the most and as women left the labor force to care for family members, that termination gap more than doubled, growing 2.1 times to 5 percentage points: 32% of women separated from their jobs, compared to 27% of men.

Table 5: Termination Rates, by Gender and Year

In order to quantify the effect of these patterns on measures of pay equity, it is important to explore how these patterns played out in 2020 across the wage distribution. The gender pay gap is calculated as the ratio of median earnings of full-time, year-round workers, so when employees leave the labor force during the year (they are voluntarily or involuntarily terminated) they are no longer included in this sample on which median earnings are calculated. Most critically, if one gender experiences significant changes in termination patterns across the wage distribution, this can alter measures of pay equity in ways that don’t reflect the true changes in economic power that the pay gap is intended to measure.

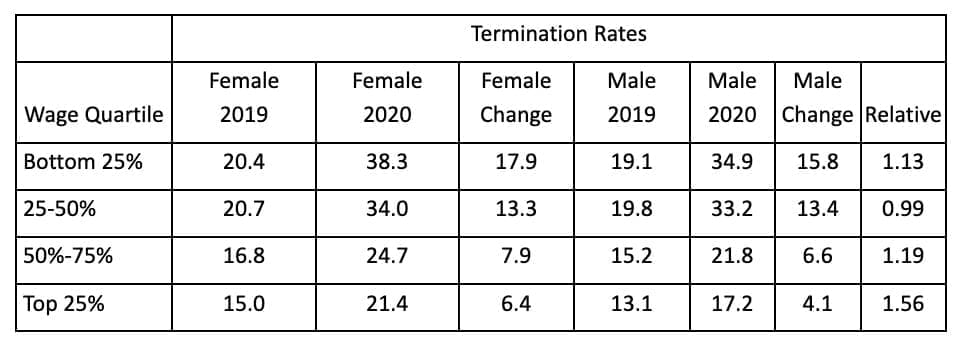

Table 6 displays termination rates across four wage quartiles, by gender, for 2019 and 2020. First, across genders, the termination gap is highest and rose the fastest among the bottom 25% of earners. But, strikingly, the termination gap rose much quicker for women in the bottom of the wage distribution, nearly doubling between 2019 and 2020 than it did for men. These dynamics offer a key insight into what is driving the narrowing of the wage gap in 2020: the pay gap between women and men narrowed slightly because the termination gap between men and women widened significantly in the lowest wage quartile (bottom 25%). Low-wage women exited work at a much higher rate, bringing the median wage for women up. Rather than a meaningful increase in the earning power of women, this represents a more mechanical increase in wages due to the struggles of women working lower-wage jobs during the pandemic.

Table 6: Termination Rates by Gender, Year, and Wage Quartile

We quantify the effect of this termination gap on pay equity in two ways: first we simulate the pay gap in a scenario in which men experienced similar termination rates as women in 2020, and we also estimate the loss in income resulting from the excess termination of women during the 2020 pandemic. First, we calculate the “excess termination rates” of women in 2020 – that is, the percentage point difference between male and female termination rates, from Table 6. In the four wage quantiles, these gaps are 2.3 percentage points, -0.01, 1.3, and 2.6 percentage points, respectively. Then, on Gusto’s platform data, we calculate a new, corrected wage gap by estimating the earnings ratio if that additional (or fewer) percent of men in each wage quantile had been terminated in 2020. The resulting wage gap is 0.737. This finding suggests that a significant portion of the narrowing of the wage gap 0.004 of the 0.017 it narrowed, was due to these disproportionate terminations — put differently, roughly 20% of the narrowing of the wage gap from 2019 to 2020 was due to the differential rates of women leaving employment across the wage distribution.

Second, in an attempt to quantify the economic impact of these unequal termination rates in 2020, we use publicly available data on the income of full-time, year-round women to create a nationally representative estimate of the excess income lost from women leaving the workforce. To do this, we take the excess termination rates of women in 2020 across the four wage quartiles (2.3, -0.01, 1.3, and 2.6 percentage points in these wage quartiles, respectively), and apply these rates to estimates of the income and number of women in each quartile from the 2020 Current Population Survey, Annual and Social Economic Supplement. Table 7 displays each component of this calculation: summing the income lost from these additional terminations in 2020 leads to an estimated $43.9 billion in earnings lost from women leaving the workforce at higher rates in 2020.

Table 7: Computing the Lost Income from Unequal Terminations in 2020

Conclusion

The gender pay gap is a metric closely watched to measure the relative economic power of men and women — but like so many economic trends, the unprecedented disruptions caused by the pandemic can render traditional statistics ill-equipped to reflect current dynamics. In the case of pay equity, Gusto data shows that from 2019 to 2020, the gender wage gap narrowed from 0.723 to 0.740. At face value, this rise seems like good news. But, digging beneath these overall numbers shows that much of this “good” news was for bad reasons. The improvement in women’s relative earnings came because women in low-wage, service-sector jobs left the workforce at a significantly higher rate. Indeed, we find that one-fifth of the narrowing of the gender pay gap was due to increased termination rates of women in 2020 — and that these termination rates resulted in the loss of an additional $44 billion in women’s income lost from this termination gap. Achieving pay equity is a critical goal, and it is important to understand the economic statistics that underlie these measures to ensure we are reaching equality in a meaningful way.