Quick Links

Key Findings

- These entrepreneurs are changing the face of business ownership – new business owners in 2020 are much more likely to be Black, Hispanic or Latinx and female than comparable data of new businesses in past years. For instance, only 3% of new business owners were Black or African American in recent years, but that number rose to 11% in 2020. Similarly, 49% of entrepreneurs in 2020 were women, compared to 27% in recent years.

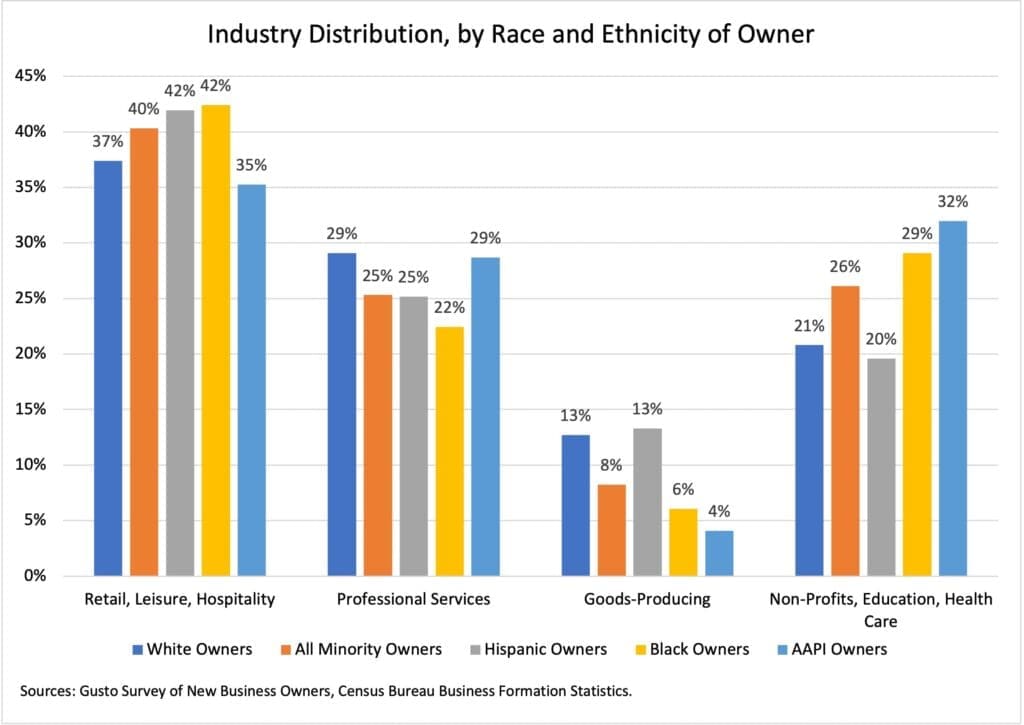

- Industry trends: Overall, the largest single sector of new business growth was Health Care and Social Assistance (16%). The largest combined sector was in Personal Services (Retail, Leisure, and Hospitality), perhaps taking advantage of opportunities as COVID reshaped the personal services economy. Women and minority owners were more likely to start businesses in the Social Services (Healthcare, Non-profits, Education) or Personal Services sectors, rather than professional services.

- Innovation out of need: 51% of all owners indicated they started their business out of an economic need, and nearly one third started the business because they lost their job. This trend persists across men and women, and all race/ethnic groups.

- Moving to the ‘burbs: There is a clear shift in business activity from urban areas to suburban areas in 2020. Nearly half (46%) of newly created businesses are located in the suburbs, compared to 2019, when just 33% of new businesses were started in suburban areas. These patterns further suggest that the pandemic-induced shift in population and economic activity away from urban cores is a long-term feature of the economic landscape.

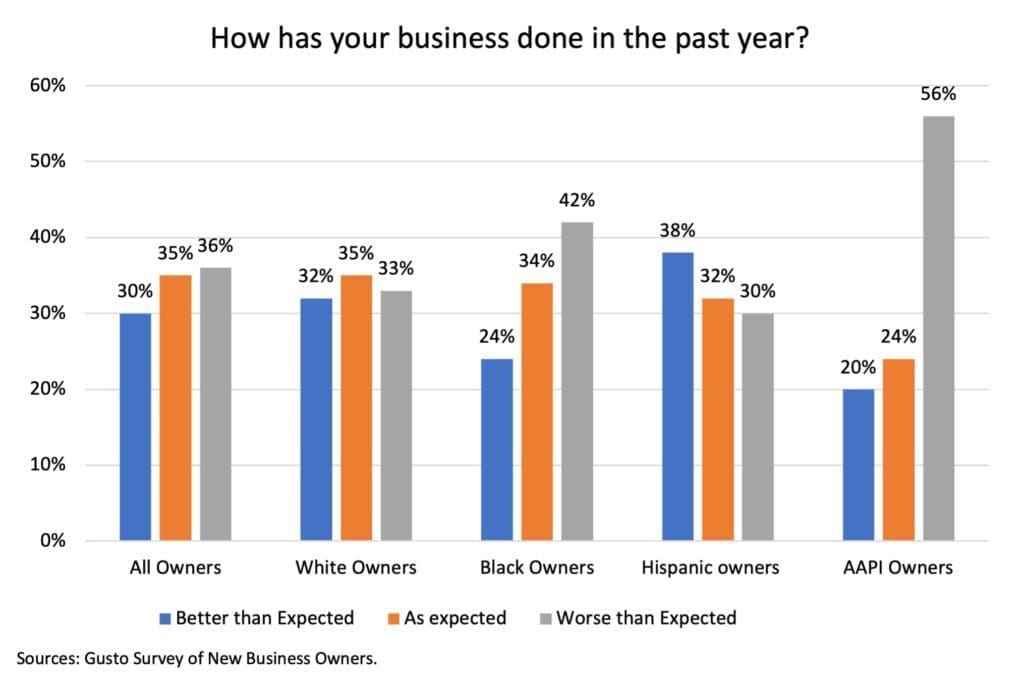

- Signs of stress from minority business owners: 35% of all owners indicated that their business is doing worse than expected when they opened. However, 42% of Black business owners and 56% of AAPI owners responded that their business is doing worse-than expected. Nearly half of these owners have cut their own wages, and, while one third of all owners have needed to take up a side job to cover business expenses, 53% of Black owners and 49% of AAPI owners have done so.

- New businesses blocked from support: Only businesses started before February 15, 2020 are eligible for Paycheck Protection Program loans, meaning nearly all of these new businesses have been left out of the government’s largest aid program for small businesses. As these businesses feel the weight of the continued pandemic, their needs have been entirely overlooked. 78% of these businesses indicated that they would take advantage of PPP loans if they were eligible, with the most common reason being that the pandemic has dragged on longer than expected.

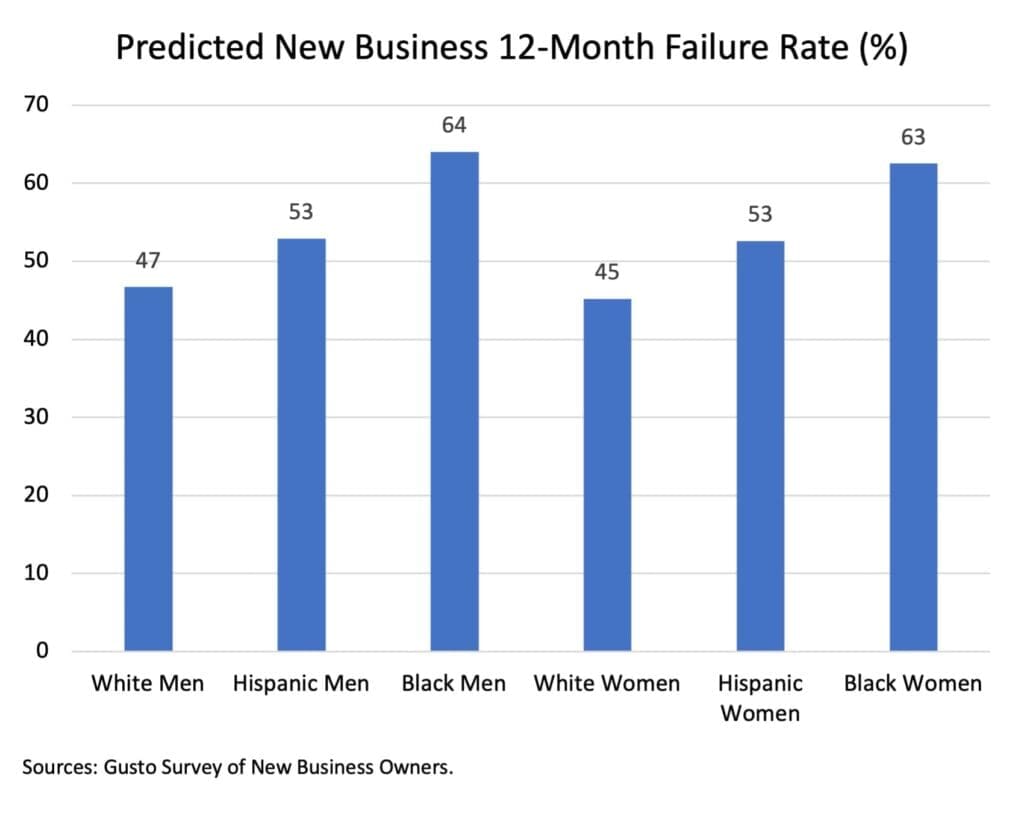

- Business failure rates were historically high in 2020. They could be even higher in 2021: recent research estimates that 130,000 businesses closed in 2020 due to the pandemic. Using the owner expectations reported in this survey, we estimate that, in 2021, new business shutdowns could be 160,000 higher than past years. This risk of closure is particularly high for minority-owned businesses. Among all owners, 51% estimate that their business will fail within the year without additional support, while 73% of Black owners and 71% of AAPI owners could fail within the next twelve months without support.

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a large toll on the US economy, shuttering small businesses and leaving millions of workers jobless. But it has brought with it one bright spot: a surge in entrepreneurship to levels not seen in a decade and a half. Indeed, according to the US Census Bureau Business Formation Statistics, there were 4.3 million new businesses created in 2020 – nearly one million more than were formed in 2019.

While this trend has received increasing attention, next to nothing is known about the faces behind these numbers: are these new entrepreneurs women or men, young adults just starting out or older workers turning to new career paths, and how are they faring after jumping into business ownership? Research has consistently found that young, small businesses are the engines of economic growth, and now more than ever it is important to fully unleash the growth potential of these new businesses. But to better serve these small businesses, and ultimately the American economy, it is crucial to understand the forces driving these trends.

Gusto, the all-in-one payroll and benefits platform for small businesses, surveyed the owners of new businesses using Gusto’s platform. Over the course of April 4-April 16, 2021, we collected responses from 1,568 business owners who indicated they started their business during the Coronavirus pandemic. We asked about their own age, race, and gender identity; why they started a business at this time; how they are faring; and how the government could best support new businesses.

We find that these owners are non-white, non-male; they are starting these businesses out of economic need; but their experiences vary greatly by race/ethnicity: more owners of color started businesses with personal savings, and as the pandemic has dragged on, they are in a much more precarious position.

During these times of economic hardship, these entrepreneurs have done all that could be asked of them. They turned adversity into opportunity, and in creating new jobs have pulled others up along with themselves. Creating a level playing field, which provides the resources for business owners to survive and thrive regardless of age, gender, or ethnicity is not only an important step to creating an economy that serves the needs of everyone, but will create a sustainable long-term recovery, as new businesses have historically been the engine of jobs growth in the American economy.

The Face of Pandemic Entrepreneurship

To better understand who these new business owners are, we examine the distribution of several business and owner characteristics, including the size and industry of the company and the age, gender, and race and ethnicity of the owner.

First, we gauge the distribution of the size of these new businesses, presented in Table 1. Among respondents, 7% were nonemployer businesses and 93% had at least one employee. The largest group of businesses (65% of all respondents) had 1-5 employees, although 18%, nearly 1 in 5 businesses, had 6-10 employees. Public data suggests that a portion of the increase in new business formation in 2020 has been driven by non-employer businesses, although these sole proprietors are less likely to join Gusto’s platform. For that reason, this analysis should largely be thought of as exploring trends among businesses with wage or salaried employees, rather than sole proprietorships. These businesses represent a crucial part of the economy, as young and small firms are the fastest-growing segment of businesses.

Table 1: How many employees does this business have?

| Number of Employees | Percent of Respondents |

| 0 Employees | 7% |

| 1-5 | 65% |

| 6-10 | 18% |

| 11-25 | 10% |

| 26-50 | 1% |

Next, we look at the identity of these entrepreneurs across two dimensions — gender and race/ethnicity — and benchmark these distributions to publicly available data on past cohorts of new business owners, from the 2017 Annual Business Survey. First, Table 2 presents the breakdown of owners by gender. These owners are about equally male and female, a striking departure from past data, where 73%, nearly three-quarters of new business owners identified as males.

Table 2: Gender Composition of Business Owners

| Gender | 2020 (Gusto Survey) | 2017 Census New Business Data |

| Male | 48.9% | 72.5% |

| Female | 48.5% | 27.5% |

| None of the above, or decline to state | 2.1% | – |

Looking at the makeup of these owners by race and ethnicity, as presented in Table 3, we see a similar break from past patterns. While in 2017, the latest year public data is available, 81% of new business owners identified as White Non-Hispanic, compared to 60% of entrepreneurs in 2020. Making up for this drop in the portion of white owners is a huge increase in the portion of owners who are Black or African American (from 2.5% to 11%) and a sizable increase in the portion who are Hispanic or Latino (from 6.3% to 9.5%) .

Taken together, these trends indicate that in 2020, as the pandemic reshaped the American economic landscape, we saw a dramatic change in the face of entrepreneurship. These new business owners are far less likely to be white and male, with minority and women entrepreneurs driving innovation throughout the year. It is no coincidence that these groups have also been dealt the toughest hand this past year, accounting for the largest portions of employment losses across the recession, as many of these owners turned to self-employment out of financial necessity. It is nevertheless striking the degree to which these individuals shifted gears in the midst of a pandemic to start a new business.

Table 3: Race/Ethnicity of Business Owners

| Race/Ethnicity | 2020 (Gusto Survey) | 2017 Census New Business Data |

| White Non-Hispanic | 60.0% | 80.7% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9.5% | 6.3% |

| Black or African American | 11.0% | 2.5% |

| Asian American or Pacific Islander | 8.1% | 10.1% |

| Other, or decline to state | 11.4% | 0.4% |

2017 American Business Survey, among owners of businesses opened for fewer than

2 years.

Next, we explore the industry distribution of these new businesses. For simplicity we aggregate sectors into four groups: (1) Retail, Leisure, and Hospitality; (2) Professional Services (Consulting, Technology, Legal, etc.); (3) Goods-Producing (Construction, Manufacturing, etc.); and (4) Social Services (Health Care, Education, and Nonprofits). The disaggregated industry composition is presented in Appendix A. Figure 1 presents the industry distribution among Gusto survey respondents, along with Census data on the industry composition of new business applicants for comparison. Encouragingly, the industry composition in this survey largely matches the publicly-available data. The largest source of new businesses growth has come in the Retail, Leisure, and Hospitality group (38%), as entrepreneurs take advantage of new opportunities in this reshaped industry. The largest portion of new businesses in this survey in any single industry is in Health Care, which accounts for 16% of all new businesses, as entrepreneurs take advantage of an increase in demand for health care services amid a public health crisis and a need for new modes of delivery (i.e. telehealth).

Figure 1: Industry Distribution of New Businesses: Gusto Survey vs. Census Data

Figures 2 and 3 break down this industry distribution by race and ethnicity and by gender, respectively. Some interesting patterns emerge in this data. Both women and minority business owners were more likely to start businesses in the personal services sector (Retail, Leisure, and Hospitality) and the Social Services Sector (Health Care, Education, and Nonprofits). For instance, while 37% of white owners started business in Personal Services, 42% of Black owners started business in that sector; while 21% of white owners started business in the Social Services sector, 32% of AAPI-owned new businesses are in that sector. Similarly, 29% of women-owned businesses are in Social Services, greater than the 17% of male-owned businesses.

Figure 2: Industry Distribution, Broken Down by Owner’s Race and Ethnicity

Figure 3: Industry Distribution, Broken Down by Gender

In a previous report, we found that small businesses in suburban areas have been experiencing a more robust economic recovery than their urban counterparts. Here we see that this divide in economic growth extends to new business creation as well. Table 4 presents the distribution of these new businesses by location type – suburban, urban, or rural area – along with comparable public data on the distribution of new businesses applications from 2019. There is a clear shift in business activity from urban areas to suburban areas in 2020, with nearly half (46%) of newly created businesses located in the suburbs.

Table 4: Location of New Businesses

| Location of Business | 2020 (Gusto Survey) | 2019 U.S. Small Business |

| Suburban | 46% | 32.5% |

| Urban | 32% | 62.1% |

| Rural | 12% | 3.4% |

| N/A | 10% | – |

Finally, we examine the reasons that these entrepreneurs started new businesses. First, we asked entrepreneurs if they started their business as a direct result of the pandemic. Many, 79% of owners, indicated they did not start as a direct result of the pandemic. 79% of such entrepreneurs who did not start their business as a direct result of the pandemic, had been planning and building their business for more than a year before opening in 2020. For these business owners, the pandemic was not an opportunity to seize but truly a worst-case scenario interrupting plans that had been long in the making, after leases were signed and savings spent.

Among those who did indicate that they started their business as a result of the pandemic, we dove into the specific reasons they turned to entrepreneurship. As presented in Table 5, across nearly every group, the most common response was some form of economic need. Among all owners, more than one-third (35%) of owners started a business because they were laid off from their prior job. Adding together answers indicating other forms of economic stress – their partner was laid off or they were generally worried about finances — more than half of all owners (52%) started a business out of economic need. Response rates across different groups of owners were broadly similar, although one notable difference did stick out: Among male owners, only 2% listed childcare responsibilities during the pandemic as the reason for turning to business ownership, while 9% of female owners did.

Table 5: Reason for starting a businesses, among those who started business as a direct result of the pandemic

| Race/Ethnicity: | You ran a previous business and voluntarily shut it down to start a different business during COVID | You were laid off from another job | Partner was laid off from their job | Worried about finances | Responding to childcare responsibilities due to the pandemic | It was the right time for this business |

| All Owners | 10% | 35% | 4% | 13% | 6% | 33% |

| White Owners | 10% | 37% | 5% | 10% | 8% | 31% |

| Minority Owners | 9% | 33% | 3% | 18% | 3% | 34% |

| Male Owners | 8% | 39% | 2% | 13% | 2% | 36% |

| Female Owners | 11% | 32% | 6% | 13% | 9% | 29% |

The New Business Divide: Differences in Experiences by Race and Ethnicity

The second part of this survey was structured as a “pulse check,” asking owners of new businesses how their ventures were performing relative to expectations and what actions they have taken to help their business along. Overall, there are strong warning signs that these owners are struggling to get by as the pandemic drags on, particularly among Black and AAPI business owners.

Figure 4 presents owners’ assessments of how their business is doing relative to their forecast, by race and ethnicity. Among all owners, there is a generally uniform distribution of performance, with roughly one-third of owners doing better than expected, as expected, or worse than expected relative to their forecast. While hispanic businesses seem to be doing slightly better than expected, there are striking skews among Black and AAPI owners towards “worse than expected.” 42 of Black-owned new businesses and 56% of AAPI-owned new businesses are doing worse than expected.

Figure 4: Has your business done better or worse than forecast when you started?

These signs of distress have translated into differences in two actions owners have taken to ensure their businesses survive while also earning a living – cutting their own pay or taking a second job to cover business expenses. Table 6 displays results from asking owners if they have cut wages for themselves since starting their business. 65% of all owners have had to cut their own wages in the past year, primarily by more than 50%, but these differences in firm performance by race and ethnicity are showing up in these actions as well. 74% of minority business owners have cut their own wages since they opened their business, including 78% of Black business owners and 74% of AAPI owners.

Table 6: Have you cut wages for yourself?

| Did not cut own wages | Less than 10% | 10%-50% | More than 50% | |

| All Owners | 35% | 4% | 19% | 42% |

| White Owners | 39% | 3% | 18% | 40% |

| Minority Owners | 27% | 5% | 22% | 47% |

| Black Owners |

23% | 3% | 22% | 53% |

| Hispanic Owners |

38% | 6% | 24% | 32% |

| AAPI Owners |

27% | 4% | 20% | 50% |

Just as alarming are the differences in the probability of owners needing to take a second job to cover expenses in the first year of operation. First, a staggering 33% of all businesses owners needed a side job to cover expenses – one in three entrepreneurs took up a second job to make sure their business could thrive (Table 7). Yet again this number spikes when looking at Black- and AAPI-owned businesses. 53%, more than half of Black entrepreneurs needed to take up a side job to make sure they could meet expenses, and 49% of AAPI entrepreneurs resorted to this step. Taken together, these patterns show that owners are committed to growing their businesses, but just as minority workers have borne the brunt of this recession, the struggles of business ownership – and the drastic actions sometimes required — are disproportionately falling on minority business owners.

Table 7: Have You Needed a Side Job to Cover Expenses?

| Percent who have needed to take a side job to cover operating costs | |

| All Owners | 33% |

| White Owners | 27% |

| Minority Owners | 43% |

| Black Owners | 53% |

| Hispanic Owners | 30% |

| AAPI Owners | 49% |

One reason that can account for this stark difference in experiences by race and ethnicity is that Black entrepreneurs were much more likely to have started business in urban areas, which continue to feel the effects of the pandemic. As noted above, 46% of all new businesses were started in suburban areas, which have seen relatively larger economic growth than urban cores. That number jumps to 49% among white businesses, while just 38% of Black business owners started their venture in the suburbs. 41% of Black-owned businesses were started in urban areas; they are the only group with a larger portion of new businesses in urban areas. As these centers continue to grapple with the effects of the pandemic, these business owners’ struggle is far from over.

The New Businesses Outlook

Finally, we asked owners to take a step back and think about the prospects of their business and the policy environment in which these ventures operate. New business ownership is a risky proposition in the best of times, with an estimated 20% of new businesses started in 2019 failing within one year, but these owners express significantly elevated levels of concern about their businesses prospects, and these concerns are highest among business owners of color. Given the pandemic has lasted much longer than expected, the vast majority of these businesses are in need of some form of additional support — and yet, because almost all were started after the eligibility cutoff for the Paycheck Protection Program, they are locked out of aid. There is a significant appetite for additional financial support among these entrepreneurs, but over 60 percent of owners feel like the public institutions are not doing enough to support them.

As presented in Table 8, without additional support, 51% of all business owners predict their business will not survive 12 months — more than twice the 20% first-year failure rate among new businesses in prior years. This rate is even higher among minority business owners: 73% of Black entrepreneurs predict their business may fail within the year and 71% of AAPI owners are likewise concerned.

These numbers are particularly concerning given the historically-high rates of business closures seen in 2020. Economists at the Federal Reserve recently estimated that 130,000 businesses closed permanently in 2020 due to the pandemic (that is, in excess of average business closure numbers in recent years). These survey results indicate that this year the US economy could see nearly 160,000 new businesses close – on top of the usual number of new businesses that typically close in one year. According to, US New Business Applications data, roughly 522,000 new employer businesses opened in 2020. In typical years, around 20% fail within the first year, which would suggest about 104,000 business closures. But this survey data indicates that the US could see new business failure rates of 51% this year, or roughly 266,000 — meaning that we could see more than (266,000 -104,000 =) 160,000 excess new businesses deaths in 2021.

Table 8: How much longer is your business able to survive without aid?

| <1 month | 1-2 months | 3-6 months | 7-12 months | I’m not concerned about my business failing | |

| All Owners | 2% | 9% | 24% | 16% | 49% |

| White Owners | 2% | 8% | 24% | 13% | 54% |

| Minority Owners | 4% | 10% | 27% | 21% | 39% |

| Black Owners |

5% | 10% | 40% | 18% | 37% |

| Hispanic Owners |

1% | 8% | 22% | 22% | 47% |

| AAPI Owners |

4% | 9% | 31% | 27% | 29% |

| Men | 2% | 9% | 25% | 16% | 49% |

| Women | 3% | 9% | 24% | 15% | 49% |

Consistent with data in the previous section, when we look at the percent of owners whose business will not be able to survive longer than 12 months without additional support by gender and race/ethnicity, we see similar racial divides within genders. For instance, while 47% of white male owners predict they will not be able to survive 12 months (which itself is an alarming number), that percent jumps to 64% among Black owners, and while 45% of white female owners predicted they would fail within 12 months, that rate also climbs to 63% for Black women (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Percent of Owners Whose Business Will Not Survive 12 Months Without Additional Aid, By Gender and Race/Ethnicity

A steady rate of business creation and failure is a constant feature of economic dynamism in the United States, and it contributes to the efficient operation of our economy. While propping up inefficient businesses is not a productive use of public resources, there are several reasons why providing additional support to these businesses is not only warranted, but badly-needed. First, the sheer magnitude of this risk indicates that the struggles that gripped existing businesses during the onset of the pandemic are holding back new businesses as well. While during the onset of the pandemic it might be argued that these entrepreneurs “knew what they were getting into,” as the pandemic passes its one-year mark that argument is far less persuasive. Indeed nearly 8 in 10 owners planned these businesses before the pandemic hit. Second, this form of innovative risk-taking is one that should be encouraged by policymakers. These owners did all that was asked of them, turning obstacles into opportunity and often putting large amounts of personal savings (including stimulus checks and unemployment insurance) into small businesses that will rebuild communities and bring others back to work in the process. Finally, there is a strong justification for additional support on equity grounds: men and women of color have been disproportionately affected by this pandemic in nearly every aspect — and the experience of these entrepreneurs is no different. Minority business owners have historically been left out of traditional forms of support, and policies to help new business owners is just one way to begin correcting historical inequities. Without such support, these business closures will only work to exacerbate historical economic disparities.

Calculating these new businesses contributions to employment can help quantify these potential gains. Economists estimate that, conditional on survival, 1-2 year old businesses have growth rates of around 15% per year. In 2021, nearly 520,000 employer businesses were formed, that’s just about 10% of all (5.3 million) firms in the U.S. Applying the number of employees among businesses in this survey to these new businesses, a 15% growth rate would translate to 700,000 additional jobs this year from new businesses alone. In 2019, the US added 2.1 million jobs all year. Thus, helping these new businesses achieve even historically average growth rates would mean that these entrepreneurs, representing less than 10 percent of all businesses, could contribute to 33% of all job gains.

How Policymakers Can Act

The quickest form of support for these new businesses would be to replenish Paycheck Protection Program funds, update the eligibility requirements to allow businesses created after February 15, 2020, and prioritize their access to aid. When asked if they would apply for a PPP loan if made available, 78% of these business owners indicated that they would. Owners estimated they needed an average of $52,343 to keep their business afloat for 12 months. Given a PPP loan is calculated to cover 2.5 months of expenses, this amount translates to roughly $11,000 – just around the average PPP loan of $15,000 for a business with less than 10 employees (as almost all of these owners are).

Thinking more fundamentally, there is a broad sentiment among owners that policymakers could do much more to support new businesses. When asked if the government is doing enough to support new entrepreneurs, only 22% said “yes” and 63% of all owners responded that they did not think so. There is a substantial opportunity for policymakers to step in and expand access to financing for these entrepreneurs: 28% of business owners indicated that in the next twelve months they anticipated obtaining new funding or capital – likely as a lifeline of support rather than to grow or expand.

The advantages of helping new business are numerous. Young, small, high-growth businesses have historically been the drivers of economic growth, accounting for nearly half of gross job creation in the United States. In recent years, the United States has in fact seen a slowdown in new business creation, contributing to a substantial slowdown in growth rates.

While the economic toll this pandemic has exacted cannot be discounted, the surge in new business creation left in its wake is one bright spot that, when supported by public policies, can contribute to a more dynamic economy going forward. Just as encouragingly, this new business creation is driven by groups that do not traditionally start new businesses, particularly women and people of color, meaning that supporting new business will not only accelerate the recovery but will help groups that have been traditionally blocked from this path of economic independence in the process.

Supporting new business can take a number of forms, but it is crucial to deliver this support in ways that are time-effective and reach these groups traditionally shut out of support programs. Specifically, policies that provide support for owners to add employees, in the form of wage credits, or policies that incentivize investors and financial institutions to support these small businesses, in the form of tax credits that can raise these investment’s rate of return are two particular forms of support that could effectively support these new businesses.

These owners represent the best of the American entrepreneurial spirit, showing resilience in the face of unprecedented obstacles. The businesses they created hold the key to a fast-growing, dynamic economic future that is inclusive of all Americans; their success or failure is truly all of our success or failure. But it is up to policymakers to provide the resources to help realize this great potential.

Methodology

Gusto surveyed 1,568 new business owners (those who indicated they started their business during the Coronavirus pandemic) from April 4-April 16, 2021. We collected responses about the age, race, and gender identity of these owners, as well as the reasons why they started a business at this time, how they are faring, and how the government could best support new businesses. Responses are weighted to match publicly available information on the distribution of new employer businesses by industry using 2020 Business Formation Statistics released by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Appendix

A: Full Industry Distribution of New Business Owners, by Subsector

| Healthcare & Social Assistance | 16.0% |

| Professional Services | 15.7% |

| Food & Beverage | 15.5% |

| Personal Services | 9.0% |

| Retail | 7.3% |

| Technology | 6.5% |

| Construction | 5.3% |

| Events, Entertainment & Recreation | 5.1% |

| Education | 4.9% |

| Finance & Insurance | 4.0% |

| Manufacturing | 2.5% |

| Non-Profits & Associations | 1.8% |

| Legal | 1.8% |

| Facilities | 1.6% |

| Real Estate | 1.5% |

| Utilities | 0.8% |

| Tourism & Accommodations | 0.7% |